Photojournalism research reframes way visuals are used

Photojournalism research reframes way visuals are used

In a culture that is increasingly reliant on strong visuals in digital and print media, new research shows that photojournalism continues to evolve and reframe why specific pictures should be used.

Kyser Lough, an assistant professor in journalism at Grady College, recently published two research papers: one studying how environmental photography could be more effective and the other examining feedback from photography competition judges and how their decisions impact media narratives.

In the paper “Journalism’s visual construction of place in environmental coverage” published in Newspaper Research Journal, Lough and his co-author, Ivy Ashe, a doctoral candidate in Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin, studied 1,330 images on the front pages of 45 national newspapers representing a year’s worth of coverage. They examined the way the environment is visually portrayed.

Lough explains that while most examples of environmental photography stereotypically focus on wide, expansive geographic pictures that provide a sense of place, this may not be the best approach.

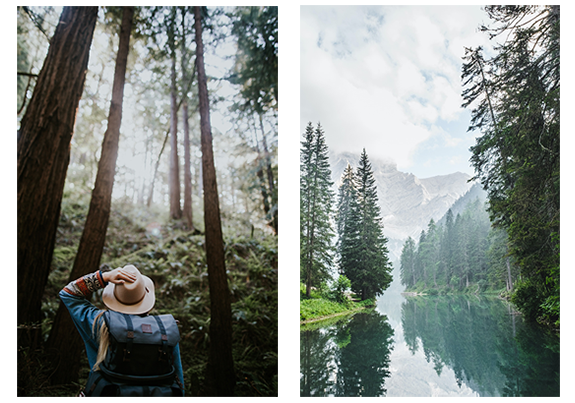

“Photojournalism needs to have people,” Lough said. “People are our community and if we are covering our community, we need to include people. People are a very important part of the environment and environmental photos because they provide scale—for instance, looking at the size of mountains or trees in the Redwood Forest compared with a person.”

“More importantly, people add humanity to pictures which help encourage more impact,” Lough said.

The researchers studied the images various ways, looking for different visual characteristics. One of these involved assigning the photo to one of four tiers in an emotional hierarchy from basic to complex: informational, graphically appealing, emotionally appealing and intimate.

As an example, a wide-angle picture of a mountain range would be a graphically-appealing picture whereas a picture that is a close-up portrait of someone suffering loss in a wildfire, is classified in an intimate tier.

Most of the photos evaluated were informational photos, but the goal is to have photos that are at least graphically-appealing emotional, if not intimate.

Lough explains it is hard to get an intimate photo of the environment because they are traditionally associated with tight portraits of people conveying a story. However, with more encouragement from photo editors, photojournalists can be encouraged to take more environmental pictures with people to make a connection.

Another implication is to aim for a more human-focused connection that prompts people to take action. Previous research has found that many people support protecting the environment, but not many act on this support. Emotionally-appealing photography could change this.

A second recent study by Lough examined the discussion between judges during deliberations at two national photo competitions: the Best of Photojournalism competition sponsored by the National Press Photographers Association which is headquartered at Grady College and the Pictures of the Year International competition through the Missouri School of Journalism.

In the paper “Judging Photojournalism: The Metajournalistic Discourse of Judges at the Best of Photojournalism and Pictures of the Year Contests,” published in the Journalism Studies journal, Both competitions open their judging rounds to the public, so Lough studied hours of this deliberation about what judges deemed as award-winning photography.

Discussions were divided into three main categories: thematic conversations where judges talked about photojournalism as a profession; discussions that focus on the photographer and his/her process; and a category that discussed the image, including story-telling qualities and composition.

Lough explains that some of the most insightful conversation took place when judges talked about the photojournalism profession. In one exchange, judges were discussing final images in the news category. The final images all represented death or suffering of people of color and the question was whether that was how we think of news and issues.

Lough continues: “I thought it was surprising and refreshing that the judges were talking about topics like that. and that the judges were asking ‘do we want to reward this’ and ‘what are the implications of us elevating this photo?’ That’s the whole thing we talk about with journalism awards—what message does this send to current and future photojournalists about what they value and how they should behave ethically and otherwise? I liked that there was that self-awareness there.”

This provides more insight and implications for photo editors, especially, in deciding what pictures they choose to print.

Lough appreciates the value of these discussions and what it brings to the education of the students who serve as volunteers at the competitions.

“The students can witness these conversations and learn a great deal,” Lough concluded. “That’s where the education is.”

Editor’s Note: Links to the papers can be found below or by emailing Kyser Lough at KyserL@uga.edu.