Eugene Patterson: Journalism icon, war hero, champion for civil rights

Eugene Patterson: Journalism icon, war hero, champion for civil rights

Editor’s note: This feature is part of the Georgia Groundbreakers series produced by the University of Georgia. Profiles celebrate innovative and visionary faculty, students, alumni and leaders and their profound, enduring impact on our state, our nation and the world.

Eugene Patterson (ABJ ’43) led his life according to his guiding motto: “Don’t just make a living. Make a mark.”

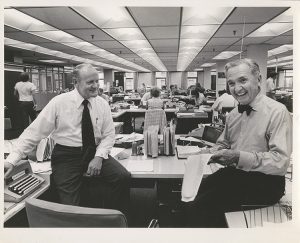

Patterson made an indelible mark in 1971 while serving as managing editor of the Washington Post. Under the leadership of legendary publisher Katharine Graham, Patterson was key to the decision to publish the Pentagon Papers, a “top secret” report on U.S. policymaking in Vietnam. The papers contained nothing of military value, but what they revealed was explosive, and the decision to publish the leaked papers led to the extensive protection and freedom of the press we know today in the United States.

Shortly before the Post published the documents, David Halberstam recounted in his bestselling book “The Powers That Be,” Patterson said to Graham: “I think the immortal soul of The Washington Post is at stake. If we don’t print it, it’s really going to be terrible because the government knows we have the Papers, and we’ll be used as evidence against the (New York) Times.” (The New York Times published the papers first, then was ordered by a federal court to cease publication. The Post took up the torch soon after when they received a copy of the leaked documents.)

Katharine’s son, Donald Graham, was a young journalist in the newsroom on his road to becoming a publisher himself when the agonizing decision was made to go against the government’s demands and print the highly charged look at how the government had handled the Vietnam War.

Donald said on the second day of printing the papers, the Post’s lawyers called the newsroom to tell them the courts had upheld the government’s appeal and the Post was enjoined not to print any more stories based on the Pentagon Papers.

“Gene told me, ‘This was the only time in my life [that] I went down to the presses and said “stop the presses,”’ Donald recalled.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court sided with the newspapers.

While Patterson risked his career with the decision to publish the Pentagon Papers, during his time as editor of The Atlanta Constitution, some of the editorials he wrote risked his life.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Cynthia Tucker, the first Black female editor of The Atlanta Journal Constitution in the 1990s, said that not only did Patterson’s writing help open doors for her professionally, but his words also resonate today. “Gene taught lessons of getting the truth out there and courageous reporting—lessons that journalists need to keep in mind.”

The Atlanta Newspapers

In 1956, Patterson joined The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution, later known as The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, as executive editor. He was named editor in 1960 when Ralph McGill was named publisher.

It was throughout the turmoil of the next several years that Patterson’s writing was most prolific and powerful. He wrote an editorial six days a week during his years at The Constitution and amassed more than 3,200 editorials at that paper alone. His words issued a clarion call that brought more understanding and responsibility to a segregated south.

“Heat and anger weigh like a weight on the land,” wrote Patterson in an August 1963 column. “[Black] and white, Americans are making easy judgements of each other instead of directing calm judgement toward the goal of racial fairness.”

In an interview with the American Society of Newspaper Editors around this time, Patterson shared his writing recipe: “Say what you think. Don’t pull punches. Don’t try to please all your readers.”

Patterson followed his own advice and his writing was most direct when he championed the oppressed, held the south accountable, took politicians to task and challenged humanity to be better.

He wrote his most famous editorial on Sept. 16, 1963, following the Birmingham church bombing that killed four young Black girls. His column, “A Flower for the Graves,” was a wake-up call for not just the south, but for America. Walter Cronkite invited him to read it on the CBS Evening News and it elicited more than 1,000 letters to the editor, many of which he kept his entire life.

His columns brought opposition as well. Patterson received hate letters in the mail, kept a ball peen hammer in his desk drawer in case he needed it as a weapon and dealt with attacks close to home like when someone shot the family dog, Lizzy, in the yard. Lizzy survived, but lived her remaining years with a bullet lodged near her heart.

Lizzy was still alive when Patterson’s daughter, Mary, was in college and introduced her future husband, Jay Fausch, to her parents. Despite growing up with taunts and jeers from kids in school because of her father’s opinions, she didn’t take it to heart.

“Mary loved what her father was doing,” Fausch said. “She was politically aligned with Gene and acknowledged he was doing good things. She really admired her father.”

“He was a voice in the wilderness at a time when being in the wilderness was unpopular,” Fausch continued. “He was able to write things in such a way to reach an audience who he knew might have beliefs different than him but who might be open to persuasion. He would look at his columns as a way of helping to right some of the wrongs in his society.”

Patterson’s legacy at The Constitution is entwined with Ralph McGill, who was Patterson’s boss during this time and had the biggest influence on Patterson’s career.

Patterson was asked in a 2008 interview with Bownwen Dickey what McGill taught him about journalism. Patterson said: “Everything that’s guided me since I first met the man. To have the courage to speak your mind even if it costs you friends and even jeopardizes your job.”

It was Patterson, too, who was the speaker at the inaugural Ralph McGill Lecture at the University of Georgia in November 1979.

“Ralph McGill is a person from whom I bore the greatest respect and affection I have felt toward any outside of my own family.”

During Patterson’s years at the Atlanta Journal Constitution, he was appointed vice chairman of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission by President Lyndon Johnson, and in 1967, he served on President Johnson’s delegation to monitor elections in South Vietnam.

Fellow UGA alumnus Tom Johnson, who served in various positions throughout LBJ’s administration including special assistant to the President and later publisher of the Los Angeles Times and CNN’s first president, said President Johnson thought so highly of Patterson that they tried to find a spot for him in public service before he ultimately joined the Washington Post.

“Gene was such a champion and such a force,” Tom Johnson said.

Patterson earned a Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing in 1967.

Foundation of Character

For someone who traveled the world filling seven passports and meeting every president from Franklin Delano Roosevelt to Bill Clinton, Eugene Patterson had a very modest childhood.

Born in Valdosta, Georgia, Patterson moved to rural Adel, Georgia, when he was young after his father, who was a banker, fell on hard times during the Depression. Patterson, along with his brother, Bill, and sister, Anne, faced the harsh realities of the era, living in a house without electricity or indoor plumbing. He worked on the family farm milking cows and plowing fields filled with arrowheads left from Creek Indians who were evicted from the land decades before the family, one of the injustices that helped cement his views on equal rights.

Patterson worked his first newspaper job at The Adel News, which led him to North Georgia College, now the University of North Georgia, where he was editor of the student newspaper. He continued to the University of Georgia to finish his journalism degree in 1943 at what was then known as the Grady School, and wrote for The Red & Black student newspaper in the opening months of World War II.

“The quarter is ending and I am in the middle of short stories, features, labs, riding hours, and general cramming,” he wrote to his mother in a February 1943 letter.

Patterson would return to Grady College multiple times throughout his life including in 1978 to accept an Outstanding Alumnus Award and in 2008 to be inducted into the inaugural class of Grady Fellows.

World War II and After

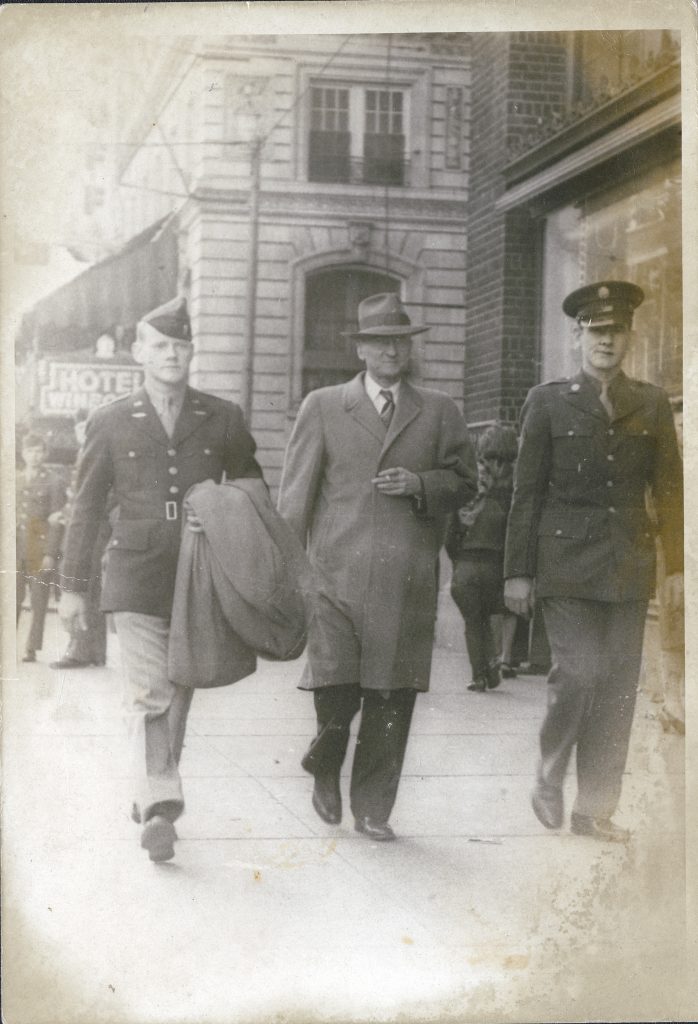

The raw aftermath of Pearl Harbor inspired Patterson to invest his time as a preflight cadet in ROTC, learning drills and jumping horses. After UGA, Patterson spent a short time at Ft. Knox, where he graduated from officer candidate school as a second lieutenant before he was sent abroad to fight.

Patterson was a decorated war hero, serving in World War II under General George S. Patton Jr. in the Battle of the Bulge. He came home with a Silver Star for “outstanding initiative and cool-headed leadership,” and a Bronze Star with Oak Leaf Cluster for “gallant achievement.”

After coming home from war, it was expected that Patterson would be a career soldier and he trained a few years as a pilot, ultimately leaving the service as a captain in 1947. He wrote that his parents were “deeply perplexed and disappointed” that he left the steady job and pension that the Army provided: “I, a professional solider with a promising future, was quitting the security of the military to try my hand at—what? Journalism. My plainspoken mother told me, ‘Son, I understand newspaper reporters are paid too little and drink too much.’

Following several reporter positions, he landed a job at the United Press, which took him to Atlanta, New York and South Carolina – where he met Mary Sue Carter, herself a journalist. They married in 1950 and after a brief stint in New York, the UP sent him to England in 1953 to assume the post of United Press London Bureau Chief. There, he reported on the beginning of the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, the wedding of Grace Kelly and Prince Ranier and the final days of the rule of Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Their only child, Mary, was born in London in 1954.

Post Washington Post

After the Washington Post, Patterson turned to a year of teaching public policy at Duke University, years before he would sit on the school’s Board of Trustees and have a journalism and public policy chair established in his name.

Soon after publishing the Pentagon Papers, Patterson left the Washington Post in 1972 to assume one of the most influential positions in the journalism industry: editor and president of the St. Petersburg Times, now known as The Tampa Bay Times. The paper won two Pulitzer Prizes under his leadership, and Patterson later served on the Pulitzer Prize Board of Directors from 1974 to 1985.

Gene and Sue were very active in the social scenes in Washington, D.C. and later in St. Petersburg, frequently hosting dinners and parties. Gene was known for belting out a strong rendition of “Danny Boy” and singing Christmas carols at their annual Christmas Eve party, always including not just immediate family but also extended family friends with whom he worked.

“Gene was an awesome tenor,” remembered Fausch, “and he could sing hymns like nobody’s business.”

In 1978, Patterson succeeded Nelson Poynter as CEO and chairman of The Poynter Institute, the nonprofit that owned the St. Petersburg Times. Patterson held this position until his retirement in 1988. Patterson also presided as president over the highly respected American Society of Newspaper Editors in 1977-78.

“To the young who may choose a life in the news business,” he wrote in his final column before retiring, “I wish them all the breadth of experience that came my way, from the blast of the rockets’ liftoffs at Cape Canaveral to the tumult of 15 national political conventions, from the silence of patrols through the Vietnam elephant grass to the thunder of Dr. King’s ‘I have a dream’ rolling down from the Lincoln Memorial.”

In addition to his 1967 Pulitzer, he was awarded more than 15 honorary degrees from institutions including Harvard, Duke and Emory.

Retirement

Katharine Graham wrote to Patterson at the time of his retirement from the Poynter Institute in 1988: “I can’t remember a time when you didn’t stand for something in all our minds, starting in Atlanta. They were things like civil rights, courage, decency and excellence.”

During retirement, Patterson fished and enjoyed being a grandfather, but he also continued to write. He returned to Europe several times to study the battlefields that were seized and bridges that were blocked during World War II, and wrote a book entitled “Patton’s Unsung Armor of the Ardennes,” in 2008 as a tribute to Patton and a remembrance of his time in the Army.

After being diagnosed with cancer in 2012, Patterson took on an ambitious project that was also, in part, an act of faith: He edited the Old Testament by half a million words in a self-published book, “Chord.”

“Gene thought the Old Testament was a great story but it was rather disjointed,” Fausch said. “He wanted to bring it to a digestible level where people could sit and read it and appreciate the flow as a story from beginning to end and grasp the important parts.”

Patterson died in 2013 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, an honor befitting a war hero. He is buried next to his wife, Sue, and in true fashion, he had all of his archives in order, his funeral planned and his epitaph written.

Under his name on the tombstone is a list of his war merits and this description: “Soldier, editor, teacher, father, friend.”